Günther Schwarberg

Why is there a Günther-Schwarberg-Weg in the Schnelsen-Burgwedel district of Hamburg? Who was Günther Schwarberg and why was he honored with a path name?

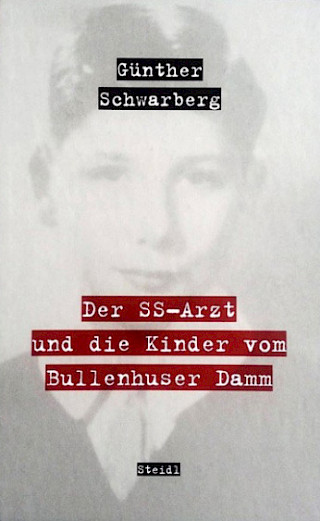

Günther Schwarberg was a journalist, his most important work probably being the story of the "Children of BullenhuserDamm," which first appeared as a series of articles in Stern magazine and was later published as a book.

Together with his wife, Barbara Hüsing, a lawyer, Günther Schwarberg traced the relatives of the murdered children. In 1979, they, along with the relatives, founded our association. They succeeded in having the murder site - the school on Bullenhuser Damm - designated as a memorial, with a rose garden planted in memory of the victims. Günther served as the chairman of our association for many years.

Born on October 14, 1926, Günther grew up in Bremen-Vegesack. He described his childhood and youth as "unhappy." His life was shaped by the traumatic experiences of National Socialism and the war. At the age of 18, he personally experienced May 8, 1945, as the day of liberation.

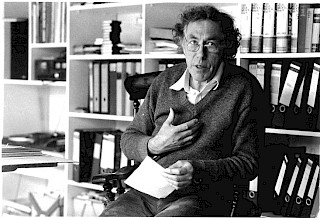

From the fall of 1945, Gunther worked as a journalist, initially in Bremen at the Weser-Kurier and the BremerNachrichten. Later, he worked at a press service, Bild am Sonntag, Constanze, and finally, for well over 20 years, at Stern magazine.

In 1977, Günther learned by chance about the murder of children at Bullenhuser Damm and realized that former concentration camp prisoners from the "Amicale Internationale de Neuengamme" had been trying to commemorate the site for years.

"But every year, they became fewer and fewer." Gunther then asked himself, "Why are you even a journalist if you don't write this story down before it's completely forgotten? Are there still parents out there searching for their children? How do you trace the story of twenty children among six million dead?"

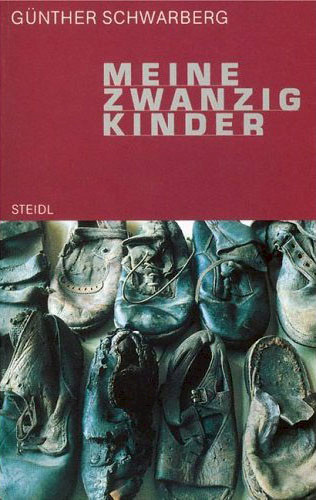

Twenty years in, Gunther continued to research, make contacts, and connect the stories with his life. Upon reflection, Gunther said, "I have twenty children... In my youth, I knew nothing about them. Back then, they could have been my younger siblings. Now, after many years, they have become my children."

He and Barbara Hüsing have given numerous lectures on the fate of the children, and created a large touring exhibition on the topic. In 1986, they organized an international tribunal that used the example of the children's murder to highlight the failure of the Federal German justice system to address National Socialist crimes.

In 1987, Günther Schwarberg and Barbara Hüsing were awarded the Anne Frank Medal for their work in 1987. Günther Schwarberg's last book "Das vergess ich nie" was published in 2007 and contains his memoirs as a journalist. He worked as an author and freelance journalist until his death on December 3, 2008.

In the Schnelsen-Burgwedel district, numerous streets, the market square, the central park area, a daycare center, the playhouse and the youth club are named after the children from Bullenhuser Damm. The Günther-Schwarberg-Weg honors the late journalist not only for his dedication, but also places Günther among "his" twenty children by name.